I've written about this procedure as documentation which we refer to at my company Intaglio Editions, and to assist those interested in achieving more continuous-tone quality from their polymer plate prints. It has taken several years of first-hand trial and error and the advice of many experts from various disciplines, cited below, for me to develop this approach. It is not for beginners, and definitely not a cheap or easy method to printmaking. Making photogravure plates in this manner requires an investment of time and money, but I hope this document saves you a great deal of both, and allows you to create beautifully satisfying, archival, polymer photogravure prints!

This procedure will not achieve the same level of detail and resolution as the holy grail of these processes: Copper Plate Photogravure. The goal of this method is to make prints that attain a level of quality somewhere in between the standard, contrasty, and more grainy-looking polymer plate prints many of us have come to expect, and those made via copper gravure, coming closer to the latter, we hope.

This procedure was also written before the innovative technique of "Direct-to-Plate" was developed, whereby the practitioner prints directly from an inkjet printer onto a steel-backed, polymer plate, before exposing and processing. While this technique is ideal for teaching the process of platemaking and printmaking, it does not produce the same smooth, aesthetic look and feel of a random dot aquatint, as with our more traditional process.

Some people have asked, "Why not do straight photography, rather than going through all this business of buying special equipment and screens, generating added frustration and expense?" To photographers who have tried intaglio printmaking the reasons are clear: Photographic chemistry is supposedly more toxic than this process (though as Dick Sullivan once pointed out, how do we truly know polymer photogravure is a non-toxic process? Well, Dick's suspicions were not off-base. The late photo artist Karl Koenig reported to me that he had used one popular brand of polymer plate for 2-3 years doing washout with his bare hands with no problem. Then one day out of the blue he developed a painfully blistering and severe skin reaction from a buildup of toxins in his skin which took many months and doctor visits to correct. Karl now wouldn't think of processing a polymer plate without nitrile gloves. I'm with him.

Health risks notwithstanding, we do intaglio printmaking for several aesthetic reasons. We do it because A) it is first and foremost, more archival than standard photography, digital or otherwise, B) it is certainly less immediately toxic than the chemicals used in copper gravure, C) it allows us to employ many creative and traditional printmaking techniques that straight photography doesn't, such as a la poupee and chin colle, and D) it offers a wider range of papers to use. Until the technology or the standard approach changes, results of this process will probably never look as sharp nor as continuous in tone as a silver gelatin or giclee print, nor should that be expected. The approach I am proposing herein has, however, brought us a couple of steps closer.

This procedure requires a computer, some intermediate knowledge of intaglio printmaking and Photoshop, a "professional" grade inkjet printer, a vacuum frame and metal-halide exposure unit, some especially fine, custom aquatint screens, anti-static supplies, and some gorgeous, high-resolution images worth printing. The exposure unit I use is an Olec 5000, using a Spectramatch Lamp model L1261, which is designed to output the precise ultraviolet light frequency that these polymer plates are most sensitive to. This documentation has been written for my particular work, equipment, and taste. Please feel free to use it as a guideline to develop your own procedure en route to making beautiful polymer photogravure prints.

- Jon Lybrook

Addendum: 2008-07-01 - The better plates we produce, the more an expert level of skill as a printmaker is required to render the subtleties and details contained in the new plates.

- Create the Inkjet Image Transparency

- Find or create an image worth printing (preferably in RGB, 16bit - working in 16bit allows your process compensation curve (discussed later) to do less damage to the tonal continuity of your image). Scan, transfer, or otherwise get your image into PhotoShop or another image-editing program that works with your inkjet printer. As of the date of this document, I use the Epson Perfection 4870 Pro scanner. Mark Nelson, author of Precision Digital Negative once posted some notes about scanning to the Alt-Photo-Process Newsgroup you may find useful.

- Cleanup and modify the image content. The clone and healing tools in Photoshop are your friends for this part of the process.

- Now that your image is cleaned up, convert the Photoshop Profile of the image to Gray Gamma 2.2 if running Windows (Gray Gamma 1.8 for Mac). This can be found from the Photoshop CS3 Menu under Edit | Convert to Profile. Profiles can undo you if you choose the wrong one, so be clear about which one has been applied to your image.

- Create a Levels Adjustment Layer, and tighten up the Head and the Toe. Don't be afraid to clip the blacks and highlights a little if it helps the image. When working with a 16bit image the amount clipped will be less than working in 8bit. Adjust the midpoint to taste but with caution.

- If your image needs further adjusting for tonal balance, create a Curve Adjustment Layer and tweak it until it looks best on your screen. If you're unfamiliar with Levels and Curves, check YouTube for a good photoshop tutorial.

- Now resize your image to 100% of the size you want at 360 ppi (Mark Nelson offers that 360 ppi provides optimum sharpness, based on the fact that it can be divided evenly into 1440 or 2880 printer driver resolutions). You should also size your transparency such that it is smaller than the size of the plate. If the transparency is larger than the plate, the transparency gets bent over the lip of the plate, causing a dark shadow along the perimeter in some cases. Keep in mind, unless you've gone to the expense of having your monitor and printer properly calibrated, and do it regularly, what you see on the screen may not look precisely like what comes out of your printer. Simple calibration systems are out there that have you compare what your monitor looks like to a color chart with accurately printed colors. This approach is often adequate.

- In order to get a broader range of shadow detail, a process compensation curve is, in fact, required to get the broadest range of shadow detail form your print. Most of the image detail is natively retained using the approach contained herein, however shadow detail will get buried in most images without an adjustment to the curve. A good process compensation curve basically lowers the contrast of the image. Contrast is then naturally reintroduced when it gets transferred to polymer plate. Without it, the image will appear too contrasty - especially in the blacks. Just as making a photocopy of a photograph increases contrast, so does transferring from film to plate. Note that you may have multiple curves applied to an image using adjustment layers (another good reason to use them as opposed to modifying the curve of the image directly). You can have one curve to adjust the overall tone of the image, then apply the process compensation curve on top of that. The latest process compensation curve I have been experimenting with can be downloaded here. This curve is a suitable starting point for images sized to 360 ppi and printed out at 1440 dpi with 'black ink only' selected in the printer driver. (Note that 'black ink only' does not use light black or light light black, in case your printer has those - it is indeed only black ink that's used. Unfortunately, when running head cleanings, all ink colors are used, which is a horible waste, but that's the cost of doing business. The good news is, if a nozzle check indicates banding with any color other than black, it doesn't matter.) It was tested using an Epson Stylus Pro 7800 printer, but the ideal curve will be different from printer to printer, even among the same model printer... Do not apply the process compensation curve just yet.

How to best derive your own process compensation curve (determine exposure times and setting levels too) can be found in this book: Digital Negatives: Using Photoshop to Create Digital Negatives for Silver and Alternative Process Printing by Ron Reeder.

- As a final check on your flattened image, open up the Threshold tool in Photoshop under Image | Adjustments | Threshold. Make sure the histogram represented covers the entire length of the graph, just as it should have been between the pointers in your levels adjustment. If there's too much white space on the head or the toe, your image is lacking 100% white or 100% black. We need this for a perfectly balanced image, so see if you see the need, go back and adjust your levels or aesthetics adjustment curve (as opposed to process compensation curve) again.

- After all your tweaks have been done, smart sharpen the image (if needed), apply the compensation curve, and then finally convert to 8 bit. Apply your process compensation curve to the final image by adding an Adjustment Layer Curve, the click the Load button, and choose the ACV file from your local hard drive. Flatten the image again.

- The image is almost ready to print. Create an empty grayscale image the size of the media you intend to use at 360 ppi, so that it corresponds to your image. Copy and paste your image into this new image. Drag guides to surround your image tightly, and then use the Rectangular Marquee tool to select only the image. Save the image as image-working-copy.psd or something meaningful.

- Make sure you leave enough of a border around the image. Printing right to the edge of the Pictorico is not recommended as it may smear.

- One final reminder: Be certain your profile in Photoshop AND in the PRINTER DRIVER are set correctly! Gray Gamma 2.2 for Windows, Gray Gamma 1.8 for Mac. If set improperly your tonal range will be sacrificed considerably.

- Finally, print your image using the Epson 2200, Epson 2400, 3800, 4800, 7800, 9800, or any of that lineage of inkjet printers on to Pictorico OHP Premium Transparency Film. For your black cartridges, be sure to install Photo Black (not Matte Black). Under the Advanced setting of the printer driver, check Black Ink Only and Print Preview, uncheck Image Smoothing and uncheck High Speed Printing. Also choose the Premium Glossy Photo Paper paper setting in the printer driver at 1440 dpi (if you are using my sample curve given above). This will dump the proper amount of ink onto the Pictorico OHP Premium stock that corresponds with the plate exposure times listed below for my process (your mileage will vary).

- Examine your transparency for dust or scratches. Lightly dust the Pictorico media with DustOff ™ or other canned air before printing. Make sure the media goes in the correct direction into your printer. The clipped corner should be in the upper right-hand corner when positioned in your printer. Do not stack the media. Load it one sheet at a time, as needed. From the Maintenance Section of the printer driver, run a head cleaning before you print to ensure no lines show up in your transparency. This uses ink, but ensures smooth tones and avoids evil microbanding. On the Epson Stylus 2200 I had to run a head cleaning before every print to ensure no microbanding would appear on my transparencies. This is not currently the case with my 7800 and I only run a head cleaning when the printer tells me to, or if I see microbanding. Let dry for 2 hours at a minimum, but ideally 24 hours. The longer dry time gives the benefit of added time for the ink to set, making it less subject to moisture, fingerprints, and scratching if you plan on transporting it before, or preserving it after making your plate. Just before using the transparency to burn a plate, I dry it with a hairdrier or in a print drier for about 20 minutes (see below).

- The transparency, when viewed on white paper in normal room light, should give a good indication about what the final print will look like in terms of density and tone, taking into account the actual print will have greater contrast. Don't make the plate until you have the transparency right!

- So, to recap the image preparation process:

- Acquire image in RGB 16bit

- Use NoiseNinja 3rd party filter (optional)

- Cleanup and modify

- Convert Profile to GrayGamma 2.2 (Windows)

- Head and Toe the Levels (clip up to 5% to help with contrast if needed, but use with restraint).

- Apply Adjustment Curve to taste

- Flatten, and check Threshold - re-tweak as needed

- Undo Flatten, resize at 360ppi, Smart Sharpen if needed

- Print an inkjet proof on GLOSSY paper, to verify it looks good and for comparison later. (The ink and driver settings we're using are designed for glossy media. Printing on matte paper will show a duller tone than what the final print should contain).

- Apply your process compensation curve

- Flatten

- Convert to 8bit

- Print onto Pictorico OHP using Gray Gamma 2.2 in your printer driver if Windows (1.8 if Mac)

^ Top ^

- Image & Screen Relationship

- As you will learn below, first we expose a dot screen (often referred to as the "aquatint" screen), then the image transparency to the plate. The screen exposure creates a consistent pattern of random black dots across the plate. The image exposure "burns off" the dots in the areas where the image is white and essentially leaves the dots alone in the areas where the image is black. But not entirely. If we didn't first expose with the screen of black dots, areas of the image that are black would wash out when the plate was developed, resulting in 'open bite'. The screen ensures a tooth where the ink can sit.

- The image and screen exposures actually affect one another on the plate. My sense is that when creating polymer plates with inkjet-produced image transparencies there is a dependency on the fact that inkjet does allow light to pass through somewhat, as opposed to imagesetter transparencies which are dead-black, opaque dots. This image translucency interacts and affects the screen exposure/dots to a certain degree. Where the screen dot overlaps with an image dot, you've got a slightly harder black dot than you would without the image exposure step, since there will be a little light coming though the transparency even in the 100% black areas of the image (since inkjet ink isn't truly opaque). If you only exposed the screen without the image exposure, the blacks you'd get would be different - perhaps exceedingly rich with a tooth beyond what you want. That's my theory at any rate. I just know when testing to get a proper exposure time to get a solid black with the screen, and did, once I determined the optimal exposure time for the image, I wound up backsliding a little and changing the screen time in the end. Exact exposure times I'm currently using are below.

|

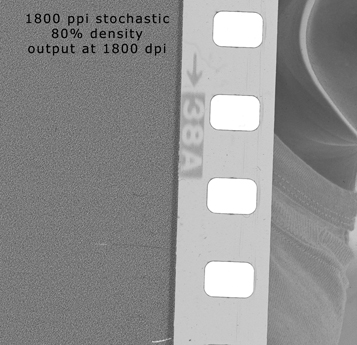

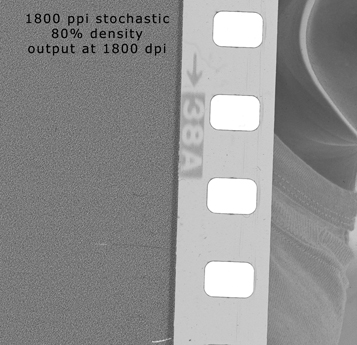

Jon Lybrook's 1800 ppi Aquatint Screen output at 1800 dpi with 35mm film beside it for comparison. Click to Enlarge

|

^ Top ^

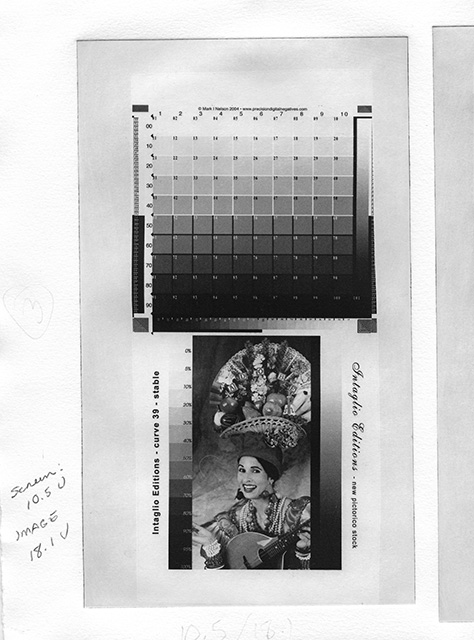

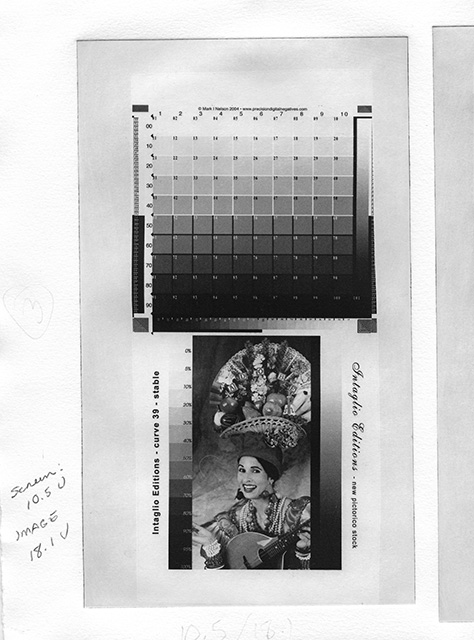

- Test and/or Expose the Plate

- When you get a new batch of plates in, don't assume the exposure will be the same one batch to the next. Age and handling of the plates could affect the exposure time. If your first plate comes out with an exposure different from what you expected based on past experience, expose a 5x7" test plate using one of Jon's step-test images or one of your own. The Adobe Fruit Lady serves as a very good referencing image. Print this test and tweak your adjustment curve whenever your printer or print head is replaced, whenever you change the kind of media your using, whenever the manufacturer changes the ink or media formulas, or whenever you change just about anything. Identical printers models may still differ in the amount of ink that gets deposited on the media.

- Determining exposure times for the very first time can be difficult. As cited above, the ratio of screen to image time is critical. But how to start? Here's a method I used:

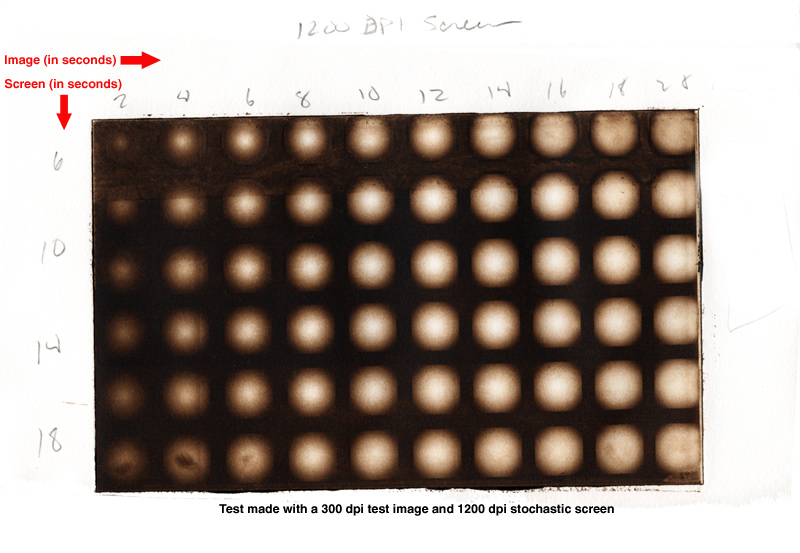

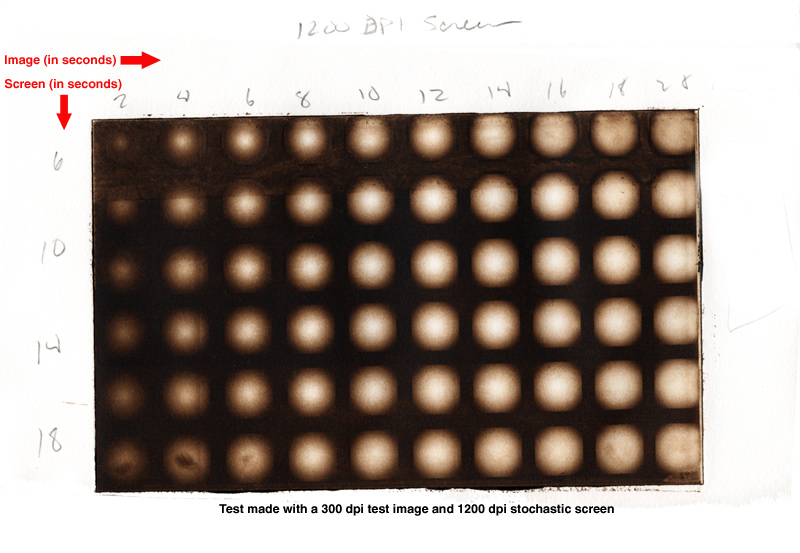

Expose a 5x7 test plate with the fine stochastic screen starting at 6 seconds at 5,000 watts and increase in 1 or 2-second increments, moving horizontally down the plate one inch per exposure. If you are using the recommended UV metal halide lamp, be sure to wear adequate UV eye protection! Once the screen has been exposed, take the gradient_circle_steptest.psd 360 ppi file (printed on Pictorico OHP Premiums tock), and expose vertically, also starting at 5 and increasing in 1-second increments. Process and print plate per the procedure below. Adjust exposure accordingly. Your times may vary depending on the available wattage of your exposure unit, age of the bulb, age of the plates, and other factors.

. .

The ideal cross-reference is going to be an evenly balanced gradient circle, like the circles in the original transparency where they are are all identical. You can see in the test above how the subsequently longer exposure time of the image (starting with 2 and ending with 20 seconds) burns away more and more of the image until you go from a nice gradient circle to an almost totally white circle. Likewise, note how the increased screen time (delineated by 6, 10, 14, and 18 seconds) goes from opaque, dark tones, to a nice balanced set of tones at 10 seconds, then to increasingly brighter, solid tone under the longer exposure times. This is because, as the plate takes on more exposure time under the screen, more light passes around the dots on the screen, and decreases the diameter and depth of the dot on the plate, which then holds less ink, and creates a lighter tone. This step test is a more economical approach to doing a standard step-test using an actual image because, unlike using an actual photograph with varying and random tones represented throughout, here, every tonal value from 0% black to 100% black, is readable in each square inch of this test, allowing for more information in every cross reference point. Final exposure times will still require a little tweaking, but the above step-test should help you to get to that ideal set of exposure times sooner. Note that in addition to exposure times, the duration time and method of processing your plate will also affect tone and density! Screen exposure, image exposure, and washout time are the holy trinity for adjusting with the physical properties of your etched plate. The next step is to derive your process compensation curve.

Once you have a good ballpark set of exposure times use Jon's step test images or the Adobe Fruit Lady step wedge to refine your process compensation curve. On the subject of deriving process compensation curves, which is beyond the scope of this procedure, one book I highly recommend is called Digital Negatives: Using Photoshop to Create Digital Negatives for Silver and Alternative Process Printing by Ron Reeder. This book goes through the steps to prepare and image and create a process compensation curve, and is one of the more up to date instructional books (as of this writing). Once you have a curve that makes your step wedge look good, the refinement is not over. You should print inkjet images (with no curve applied) and compare them to your photogravure prints and use them, with your step wedges as reference, to further tweak the curve to handle real-world images.

The ideal Step Test will have a progressive range of tones, from the blackest black, to the whitest white and as many tones as possible in between, each step as distinctly different as you can make them. This is where experience in the craft of printmaking comes in handy. I like to evaluate a step test by printing it at least three times with Charbonnelle Carbon Black ink, with little or no easywipe. This allows the plate to become seasoned somewhat and gives an opportunity to see what the plate is doing with no fancy additives or ink combinations to throw things off. "Black is truth", as Dan Welden once said.

Once you see how the plate responds to the straight ink, evaluate the tones. If they're too blocked up in the black range, add a little extra easy wipe or 00 burnt plate oil. This should open up the range of black tones. If your whites become too dingy, back off on the plate oil, which can add extra and sometimes unwanted plate tone. Tint base extender may be used to thicken up the ink and bring back more solid whites. You can also try wiping the plate longer (without over-wiping). I sometimes get a nice result from 10% easy wipe, 10% 00 burnt plate oil, and 5% tint base extender added to the Carbon Black ink. Its alot of additives, but sometimes they are called for. It depends on the piece, but in the case of testing, we are trying to bring out the greatest range possible. It helps evaluate our curve and exposure times, as well as the things we may want to do to our ink to bring out the greatest range of tones when we're printing something other than tests. If you've tried all the printerly tricks and it still doesn't look right. Take your best test, and adjust your curve or exposure times as needed, and do another test.

There were times when I and the people who know me wondered if I was ever going to be printing anything OTHER than tests. Well, that day eventually comes...until your printer or exposure unit dies, or the manufactuerer changes the formula of your plates or transparency stock...then you have to test again to get back to where you were, alas. But each round makes recallibration all the easier.

Thanks to Mark Nelson and Precision Digital Negatives for his 101 Step wedge. His Precision Digital Negative process is extremely well considered and works with all alternative photo processes.

|

Click above to view larger image

Download 84MB Zip file of a 720 DPI TIF of this image

|

- General Guidelines for exposing polymer photogravure plates:

- I use Printight model number KM 73 by Toyobo. For a richer, more painterly look, use SolarPlates™.

- Expose transparency emulsion to plate emulsion.

- The longer the image exposure, the lighter the image.

- If your blacks at 100% are flat and grey compared to lighter blacks in your image, AND the structure of the plate in these areas looks gritty, yet still washed out, either your screen or image exposure time is too short.

- On the other hand, too great of an exposure time with either the screen or image gives increasingly flatter blacks, yet the plate's structure in these areas appears solid and flat, until it becomes white (light sneaks under the dots making them increasingly smaller with less depth).

- Note: If you are planning to print colored inks, you will generally need a process compesnation curve or plate process that provides more contrast, since colored inks appear less contrasty than black.

- A point-source metal-halide light source is the best approach for this process. UV blacklight tube bulbs, while easier to acquire, are too diffuse and prone to problems. You have been warned.

- For 'aquatint screen' use an 80% density 1800ppi screen (output at 1800 dpi) screen with the plate models by Toyobo listed below.

So, where can you get an 1800 dpi aquatint screen? I wish I could tell you. Intaglio Editions had ours produced by one of the few remaining firms that had the capabilty to produce such high-resolution imagesetter film. We had them produced in large quantities, but not enough to sell commercially (nor were we interested in being in that business). I had been recommending that firm until I learned they were not delivering quality screens to the people I had referred to them. Since then we've combed the globe and have been unable to find any firm with a well-maintained imagesetter employing someone who knew how to use it. So, we are currently without a source. I have seen very nice continuous tone produced with coarser aquatint screens, so until a new source of comparable technology to imagesetters becomes available, I would encourage you to see how far you can get with them. Mark Nelson began selling very high quality screens in 2010. They cost a little more than those you can buy from printmaking supply companies, but his have a more balanced stochastic dot pattern (no clumps of black dots).

| Ink Color | Toyobo Plate Model | Image PPI | Watts | Screen Exposure | Image Exposure | Washout Time |

|---|

| Black | KM73 | 360 | 5,000 | 10.5 units | 18.1 units | 47 sec * |

| Colored | KM73 | 360 | 5,000 | 10.3 units | 15 units | 60 sec |

| Black | KM83 | 360 | 5,000 | 13.1 units | 22.6 units | 47 sec * |

*47 seconds equals about 52 full passes on an 8x12" plate with a soft nylon brush. Make sure the brush you are using remains soft as they become harder over time and should be replaced every so often. Hard brushes can mar the soft surface of the plate during washout. Processing time for larger plates will vary depending on size of plate.

Note that the KM83 plate requires 25% more exposure to both the screen and the image positive compared with the KM73. the KM73 means the layer of polymer is 73 mils (thousands of an inch). The KM83 plate is 83 mils.

Exposure times for 1,000 watts will be four times that of the exposure times at 5,000 watts.

Exposure times for 3,000 watts will be twice that of the exposure times at 5000 watts.

All exposure times are in Units (not seconds). We use units of light since the amount of exposure in a fixed amount of time theoretically changes with the condition and life of the bulb. These exposure times are just a guide. You should test, as shown above, to narrow down the exposure times required by your particular equipment.

- Use vacuum frame without glass. I retrofitted mine and replaced the glass with a layer of Kreene plastic taped to the frame and sealed using foam core around the perimeter of the frame above the bed. This was recommended to me by Harold Kyle, owner of Boxcar Press. It works great! Generally used for letterpress plate making, Kreene allows for better detail rendering, such as serifs. Another advantage is you to feel the film and plate through the plastic with your hands to detect any grit or debris that you might not otherwise be able to find. Stop the vacuum and clean away any such debris before exposing either the screen or the image. I also have a bleeder cord running in the area of the vacuum holes on the bed. This prevents the Kreene from getting sucked onto the hole, preventing adequate pressure from building up. Bleeder cord can be made from string, or the ribbed plastic cord you use to hold a windows screen to the frame. I also have a piece of flat plastic (not Plexi - thinner) laying on top of the entire bed. This prevents the rubber nubs in the blanket of the vacuum frame from embedding themselves in my aquatint screen or Kreene. The Kreene plastic may need to be replaced from time to time as it gets dirty or acquires pinholes.

- Before exposing, clean and thoroughly anti-staticize the Kreene plastic, vacuum frame bed and each transparency. Impress, and other excellent anti-static products are available from Modern Solutions. Lightly mist a rag with Impress Anti-Static Spray and clean the bed and Kreene - above and below. Spray Impress on Flexo-wand and rub it into the fabric with a clean rag, then run the flexo-wand lightly over the plate emulsion side of the screen and transparency.

- Remove protective mylar from plate and place plate on bed. Lay aquatint screen on plate. Close vacuum frame and power on. Smooth out air bubbles with Flexo-wand and feel plate through the Kreene for debris. Make sure all air has evacuated. Wait 3 minutes or so and power on light to expose the screen to the plate.

- Pictorico OHP Premium transparencies and the KM73 plates are particularly vulnerable to dreaded Newton Rings. Regular film, such as the screen made from an imagesetter doesn't have such problems, however. If you have problems with dark or light patches invading your image in the smooth tone areas, make sure you are drying your positive OHP transparency for 20-30 minutes using a hair drier or print drying cabinet. This gets rid of moisture contained in the OHP and reduces the tackiness it seems to have with the fresh KM73 pates. Additionally, after drying the transparency, apply a thin layer of baby powder to the plate and remove excess with a drafting brush, then do a final pass with a hake brush. After exposing the screen to the plate and dusting it, return plate to the bed of the vacuum frame. Cover with the freshly dusted transparency and check for debris. Smooth sandwich with Flexo-wand.

- Close frame on top of screen and plate. Turn on vacuum, smoothing Kreene plastic immediately over the plate and film. Wait for all air to escape and then wait another 15 seconds before exposing. Vacuum pressure should be around 10-14 psi or greater before exposing. Expose Screen first, followed by Image using the same procedure. Some people have said exposing the image before the screen is better. I don't believe it matters.

^ Top ^

- Process the Plate

- Get a shallow developing tray and using waterproof glue, adhere sheet magnets to the bottom of the tray. This makes an excellent processing tray as the steel-backed plates will stay in place better. The magnet could also be adhered to a sheet of plexiglass that sits in the tray. To process, put plate in tray and cover with water. Water should be about room temperature. Scrub lightly using a soft flat brush with little pressure, using various short, circular motions, for 45 seconds. Douse intermittently with water. Scrub longer than 45 seconds if you want a darker, more heavily etched plate. Be consistent when working out your washout time. Scrub too long and the darker areas of the plate may washout too much, causing then to become a dull gray instead of a velvety black.

- After about 45 seconds, remove plate from tray, rinse, then drain and blot on clean, smooth newsprint. To blot, put the wet plate face up on flat, clean newsprint. Cover with more newsprint and without pressing too hard, use the side of your hand to squeegee water from the front of the plate to the newsprint. Be careful not to cut your hand on the plate when handling the plate! Lift plate and reposition on another section of dry, clean, flat newsprint. Repeat 1x. Plate may stick slightly to newsprint, but shouldn't be too sticky. A very sticky plate means it wasn't exposed long enough. Peel paper gently from plate.

- Dry the plate with a hairdrier on hot for 3-5 minutes, then dry on warm or put it in a print drying cabinet for an additional 10 minutes at 122-140 degrees. This, along with the next step, helps temper the plate to prevent scratches.

- Post-expose plate for 10 minutes at 5000 watts, or put in direct sunlight for the same amount of time or longer.

- Examine the plate. One of the qualities copper Photogravure has going for it over standard polymer processing is a relief on the plate that has three-dimensionality to it. This relief can also be acquired with polymer when done properly. If you look at the plate on an angle in good light, you should be able to see and feel a slight depth and texture. The solid black areas should have some depth and an even, somewhat coarse texture. A well made polymer plate will have that same quality. If the blacks have an uneven texture and quality about them, you are probably under exposing your screen or over doing the washout time of the plate.

- File down and sand corners and edges of plate using wet-dry sandpaper. It minimizes ink lines around the printed image and prevents finger cuts.

- Never get the plate wet with water once it's been processed. It will mottle the image.

^ Top ^

- Prepare the Paper

- Ideally paper will be prepared in a wet pack the night before. This can be done by immersing each sheet of paper in a tray of water and letting it soak for about 30 minutes. Collect all the paper in a neat stack in the tray and lift it all at once and drain it completely, until your arms ache from holding it. Place the stack on a sheet of vinyl and fold it over the paper. Use a piece of plexiglass to support the vinyl bag and slide the whole thing into a large garbage bag and seal with tape. The next morning your paper should be wonderfully suitable for printing. If done correctly, the paper should not need blotting. The first sheet in the pile may need a quick spritz with water to rehydrate it a little, but it should not be glistening. Properly prepared printing paper should be like a "cool kiss to the touch", according to Paul Taylor of Renaissance Press. Not too damp, not too dry. Use a small hand towel to buff up the paper fibers a little bit which helps it to receive ink better.

- A more convenient, but less professional approach is to soak paper as you go. This is handy if you're only making a few prints. Soak BFK Reeves paper for no more than 1 hour. Too much soaking time can cause your problems with how the paper accepts ink, and how flat the paper dries. As always, be consistent if you want consistent results! Soaking Hahnemuhle paper for more than half an hour is not recommended. If the paper wrinkles or creases, the pressure is probably too high or the soaking time too long. I also love Hahnemule Ingres paper which is more tissue-like and should be sprayed with water completely, left to sit for 5-10 minutes, then carefully blotted before printing. Other papers may work well too, but these have worked the best for this process among the ones I've tried. Blot paper between blotter paper or cotton towels using your hands, or a heavy roller until semi-dry. Paper should be damp, not glistening.

^ Top ^

- Prepare the Tarlatan

- Prep the tarlatain the night before. The fine stochastic screens I use create a very delicate aquatint, especially in the soft highlights. To avoid scratching the plate I soak the "light" tarlatain in room-temperature water for 25-30 minutes, agitating once in a while to remove the scratchy starch. I then wring it out and hang it to dry overnight. The next morning, pull apart the tarlatain, then form it into pads.

- Set up the Press - adjust pressure

- With plexiglass in place, Position bed in middle. Raise pressure and align blankets - thinnest on bottom.

- Adjust the pressure of the intaglio printing press. Note that these plates generally need more pressure than other types of printmaking plates required to get a good transfer. I generally make it hand tight, then crank down a little bit more as needed. If your print is too weak, or displays noise in areas where it should be smooth, continuous tone, you probably need to increase pressure. If your paper wrinkles, the pressure is probably too tight or your soaking time is too great.

- Run press to the left, then right, then left again to ensure the blankets are positioned properly.

^ Top ^

- Ink and Wipe the Plate

- I recommend reading Chapter 9 - The Printing Process of Copper Plate Photogravure: Demystifying the Process for the best procedure I've found on actually making intaglio prints. The amount of care and work that goes into making copper plates easily exceeds what's required to make acceptable quality polymer plates. The printmaking process remains basically the same with either kind of plate, however.

- Wear latex or plastic medical gloves. Ink, especially red or yellow, contains nasty hydrocarbons and chemicals that can cause cancer over time. If you get ink on your skin while working, be sure to scrub it off regularly.

- Put a conservative amount of ink onto glass table (I've been using Charbonelle Carbon Black with 5-10% Easy Wipe, which produces, deep rich blacks and leaves a bit of plate tone, which can be nice).

- Roll ink onto the plate using a brayer.

- Work ink into the plate initially with prepared tarlatan with a twisting motion of the wrist, lightly grinding the ink into the tooth of plate. Do not use tarlatan which has hard ink encrusted in it as this may scratch the plate. Pick up the plate and wipe the edges thoroughly. Now put the plate face down and wipe off any ink from the back. This can get into your borders if not removed. Follow this by gently wiping with clean tarlatan in a circular motion to pull up the majority of ink and smooth it out. Follow this with a tissue paper wipe to control and smoothen highlights. Wipe with the palm of your hand briskly to remove any additional streaks or grit on your plate. As a final touch, if the image is looking to flat, the printmaker may employ retroussage. This involves taking a clean piece of tarlatan and lightly dragging it over the cleanly wiped plate in a random pattern. Retroussage cleans up and smoothens and remaining micro-clumps of ink in a random fashion. For a stronger effect, retroussage the plate while it is hot, by placing it on a heating pad. Different wiping substrates, techniques, inks, ink additives, and pressure will greatly affect the way your print looks.

- Wipe edges with flannel rag; I prefer to start with my index finger under the rag, on a slight angle above the plate and wipe either toward or away from myself. With each subsequent pass over the edge, change the angle so it moves the ink toward the back of the plate. When rag comes back relatively clean with your edge wipe, flip plate face-down onto clean newsprint. and wipe back with rag too. Then double-check and rewipe the edges, to ensure any ink that may have gotten pushed from the back to the edges of the plate is removed.

^ Top ^

- Make the Print

- Put inked plate face-up on plexiglass registration plate on the bed of the press (reverse side marked with outline of plate and paper size).

- Lay paper over plate such that the paper's deckle (and weave) is going in the same direction as the bed of the press. Running paper through the press in the other direction will cause a warping of the paper during drying. Cover with two sheets of heavy-weight, rough, clean newsprint. Lay blankets. Run through press. Move through the press consistently and not too quickly. Do not stop once the press is in motion or you may leave a heavy roller mark on the print.

- Remove paper from press. Let dry 48 hours with 7 days being ideal for black ink, 2 weeks for certain colored inks, (or let dry 1 hour and put between sheets of newsprint and carefully transport the work).

- Modify inking as needed to affect print as desired. Remember that colored inks require more saturation in the plate in order to look as dark as black might. If you plan on using brightly colored inks, make sure your plate has enough saturation capacity to take on more ink, otherwise it may look too anemic. For this reason, you will need to develop a separate process compensation curve if want to use colored inks effectively with the proper level of saturation.

- Prints generally dry darker in the blacks and appear brighter in the translucent white/gray areas after drying. They also increase in contrast.

^ Top ^

- Flatten and Dry the Print

- Flattening your prints while drying them can be accomplished by laying the print between sheets of corregated cardboardwhich are separated by sheets of Upson Board (also known as Upsonite), which is available from most building supply stores. Once dried, this gives a crisp, professional, and finished appearance to your work. A fan, shrouded in plastic is used to force air through the corregations in the cardboard and provide a steady, warm flow of air.

- A very comprehensive description of how to create a forced air print drier may be found on the Crown Point Press website.

^ Top ^

- Evaluate the Print

- If all went well, your print should look very close to the look of the transparency you used to make the plate, but with more depth and contrast. Note that the third or fourth print will have substantially less watermarks and noise than your first couple! If the blacks look good on your transparency, but are falling off in your print dramatically, you may need to re-test and re-adjust your levels, curve(s) and/or exposure times.

- The brand of paper used, soaking time, and pressure settings of the press will greatly affect how your print will look. If your print appears to grainy or patchy even though your plate and transparency are not, you may want to reevaluate the paper, or amount of pressure you are using. A considerable amount of pressure is required to get good prints using a fine aquatint screen like the one recommended. Some papers that work well for certain kinds of printmaking may not work well at all for this kind of continuous tone-looking polymer photogravure.

- If your transparency matches pretty close to your print, but you want to adjust it further, one approach is to scan your print, then take a density reading of certain areas you are interested in changing, using the info palette in photoshop. Figure out how much darker or lighter you need those points to be, and adjust your process compensation curve accordingly. Reprint your transparency, with the curve applied and the necessary adjustment should follow.

^ Top ^

- Clean the Plate

- A good cleanup method recommended by Don Messec is to put the plate on clean-ish newsprint. Spray Soy Solv II onto the plate. This is a solvent that's very gentle on the plate's finer matrix. Rub it into the plate with (gloved) hands, sop it up with clean newsprint. Repeat. Run through press onto 4 layers of clean newsprint. Do a final light sprinkle with mineral spirits, blot with clean newsprint, then run through press onto clean newsprint. Seal in plastic and store in a cool dry place, flat and horizontally. Some people coat it with a little sewing machine oil to keep the plate from drying out entirely, but I've not tried that with these plates.

^ Top ^

- Clean up the workspace

- Scoop ink off glass with putty knife and wipe into plastic wrap (ink, once removed, should never be put back into can).

- Clean glass with Low Odor mineral spirits or baby oil.

- Do final wipe of glass with windex.

- Spray ink can with anti-skin stuff to keep from drying out.

^ Top ^

- Troubleshooting

- Patches (light or dark) are often caused by improper contact between the plate and the film. In my vacuum frame retrofitted with Kreene, at Colorado's altitude, I'm able to make good plates with 12 psi. Even with a vacuum frame, however, the material needs a little help. Be sure to dry your positive transparency for 20-30 minutes in a print drying cabinet or hairdryer on low heat. Also give a light coating of baby powder (see above for the method of applying it) to the plate (and the transparency if necessary) before exposing the image. This provides a buffer to prevent the kind of patches shown below:

Print demonstrating lack of good contact between plate and film.

Do not confuse lack of proper contact with the amount of pressure required. In using a vacuum frame for this process, you shouldn't need alot of pressure. If you're having problems with dark dots or patches (often caused by newton rings), added pressure will not necessarily solve the problem (but may make the dots smaller and darker under added pressure).

- Prints that are fuzzy or that have grey tones not in the transparency may be caused by having the exposed the wrong side of the image transparency to the plate.

- Prints that have visible dot patterns or grey tones that aren't in the transparency may be caused by having the exposed the wrong side of the aquatint screen to the plate.

- Prints that are too light in tone are usually caused by over-exposure. Adjust your screen and/or image exposure times appropriately.

- Prints that are too dark in tone are usually caused by under-exposure. Adjust your screen and/or image exposure times appropriately. It may also be that your process compensation curve is not providing enough of an adjustment in the darker regions of your image curve.

- Breaks in continuous tone are sometimes the result of paper not being damp enough and/or not enough pressure on the press. If there appears to be white noise in areas that should be smooth in your prints, you may want to consider using a wet pack to condition your paper ahead of time and/or increase the pressure.

- Solarization/Posterization (or the look of it) is generally caused by improper exposure of the screen and/or image. Areas of the image that should be black are coarser and rougher on the plate as they are not exposed well enough to create a solid dot. Areas slightly grayer in tone are letting through more light, which hardens the plate properly in these areas, that subsequently holds more ink, appearing black.

Print demonstrating the "solarization" effect of improper exposure times.

- A Note about Black Light Exposure Units - I have never been able to get a black light exposure unit to work adequately, even when using a vacuum frame for better contact. They are fine for making relief plates or small photo images, or in conjunction with coarser dot screens, but images larger than 4x5" using the finer screen as recommended in this procedure has produced problems with contact, dark dots, and overall consistency. I do not recommend them for this process any longer, although I've used them successfully for platinum/palladium printmaking.

- Scratches in Transparencies of a superficial nature sometimes occur on either the base and/or emulsion side of your transparencies. These are to be expected and generally do not cause any problems if you are using a point light source for your exposures. If, however, you start to see scratches that are deep and pervasive across the entire film in the direction of the media's path through the printer here's something to try if you have an Epson wide format printer: Epson sells a high tension spindle that solved this problem for me. I bought it when I first got the printer and only used it as a last resort in an attempt to fix massive scratches on pictorico film which developed with increasing frequency over time. Just search the Epson site or your favorite vendor to see if a 'high tension spindle' is an option for you.

- Unexplained patterns in your prints are sometimes casused by the blankets on the press. Always be sure to use pressed wool blankets (never woven). We had a problem recently where a repeating line pattern was being transferred from the pusher blanket, through our two sizing catchers, through the back of the paper, and appearing on the print. We replaced our woven pusher blanket with a pressed one and the patterns disappeared. If your blankets are old, have them drycleaned or replace them and see if the mystery pattern goes away. You may also try using heavy, dry, fine art paper, such as Rives BFK as a cover-sheet or backing to your print. Smoother than blankets, having such a backing is vital when printing on thinner tissue paper and results in very smooth tones.

- Warped prints, or prints that won't flatten properly may have gone through the press the wrong way. Ideally paper goes through the press in the direction of the factory deckel, which generally ensures the paper is moving through the press with the grain of the paper. Calendaring the paper before printing is also an effective way to prevent warped prints.

^ Top ^

- Links

- The following links are to some of the most excellent artists, teachers, and vendors I've come across in this endeavor. Many of them teach workshops, and all are highly recommended.

- Intaglio Editions is my company, offering printmaking and plate making consultation and services.

Improve your Photogravure Prints with Intaglio Editions!

- jonlybrook.com features the artwork I've created en route to developing this procedure. In spite of my interest in achieving photographic realism with intaglio printmaking, my primary interest is in abstract expressionism.

- Grafisk Eksperimentarium is a traditional printmaking shop located in downtown Copenhagen, Denmark. They are a key European supplier for polymer photogravure supplies, quality aquatint screens, and DIY plans to build effective exposure units from parts that can all be aquired at Ikea!

- Henrik Boegh, owner and lead instructor of Grafisk Eksperimentarium is a well known author and artist in the printmaking world. Since he established The Printmakers' Experimentarium in Copenhagen in 1997 he has been working diligently to spread the techniques of Non-Toxic Intaglio all over Europe, South America and USA.

- Brian Pawlowski's Blog contains alot of good insight into this process.

- Renaissance Press run by Paul Taylor in New Hampshire has been particularly helpful in his command of traditional copper gravure and attention to continuous tone. Paul, like many of us, is working on finding a reliable source for a fine grained aquatint screen, usually output by an imagesetter. Quality imagesetters and people who know how to run them are fast becoming a thing of the past. If you know of any reliable sources - Contact Paul.

- Keith Taylor's website - Keith is a wonderful photographer and photo technician, employing many different processes to create outstanding photoimagery. His kind advice and experience was invaluable in getting my process relatively bug-free.

- Christina Z. Anderson - Photography instructor and author, Chris' work is diverse, meticulous, haunting and humorous.

- Angela Faris Belt - Accomplished fine arts photographer and instructor, Angela's pursuit of polymer photogravure was prompted through an allergy she developed to photochemistry.

- Clinton Cline (RIP) - Clint was full time Faculty at CU Boulder and head of the Printmaking Department for decades. His in-depth knowledge of printmaking and constructive feedback has been incredibly helpful.

- David Hoptman - Artist, Photographer, and Printmaker David Hoptman pioneered the use of the finer aquatint screen for use with photographic images, with help from Don Messec.

- Making Art Safely is Don Messec's consulting firm specializing in workshops and consultation on the safe studio design and production of art.

- Dan Burkholder's Website - Dan is the author of Making Digital Negatives for Contact Printing, and is the main pioneer in that field. His Tiny Tutorials on Photoshop are downloadable gems of wisdom.

- Dan Welden's Solarplate Website - Dan is the printmaker who first discovered the use of Polymer plates for intaglio. His workshops and book, Printmaking in the Sun, are excellent resources for beginners.

- Mark Lunning runs Open Press, Ltd. - a Fine Art Printmaking Facility in Denver, Colorado. Mark is well versed in all forms of traditional printmaking.

- Research by Peter Mosely of the Royal Photographic Society - His Doctoral Thesis: "The performance of the print".

- Boxcar Press - Distributor of the Printtight KM73 plate and other polymer plate services and supplies.

- Precision Digital Negatives by Mark Nelson is the definitive, state-of-the-art process for creating digital negatives for alternative photographic processes using chromatic density, instead of black ink, to block light.

- Pictorico is the company that makes Pictorico OHP Premium transparency stock, which is recommended for making digital inkjet transparencies using this procedure.

- The Alt-Photo-Process Mailing List out of Saskatchewan is an amazing resource of people with enormous experience in all forms of alternative photography.

- Bostick and Sullivan - They sell supplies pertaining to, and have a wide range of knowledge about, many alternative photographic processes.

- Takach Press - Dave Takach and family have been in the business for over 30 years and make the best intaglio presses on the planet.

- Refurbished Exposure Units are sold by Larry Hall of RM Services in Denver, Colorado 303-941-0687. Larry is the Olec repair tech to the stars here along the front range of the Western U.S. Both Larry and Don Messec out of Santa Fe sell refurbished metal-halide exposure units with vacuum frames (which are required for this procedure). You can expect to pay between $1,000 and $3,000 for a refurbished unit which, when new, go for well over 10K. You can also buy used ones on Ebay. New plate burners start at around 5K.

- Cheap newsprint from Uhaul!

- Self-Adhestive Sheet Magnets for putting on the bottom of processing trays and on the front of boards for inking can be found at Custom-Magnets.com. I get the thickest size.

- Great Registration System...

- Very effective print Drying and Flattening System used by Crown Point.

Intaglio Editions

Recommended Current Books and Reading

Performance of the Print - Peter Mosley's PhD thesis on texture and other qualites pertaining to historic photographic processes, such as photogravure.

Easy Digital Negatives by Peter Mrhar. Hands-down the most comprehensive way to get acceptable results with film positives quickly using tools as simple as a scanner and as precise as a spectrophotometer. No RIP or changing out your printer cartridges required. The author has made the javascript program he wrote to make the process compensation calculations free to use here.

A comprehensive and thorough manual on how to get excellent results with polymer photogravure using a variety of traditional and creative methods developed by the author.

|

Clay Harmon's excellent book Polymer Photogravure delving into the practice and artists employing polymer photogravure.

|

^ Top ^

© 2006-2024 Chronosynthesis Productions, Inc.

This document may not be reproduced in whole or in part without expressed written permission of Jon Lybrook.

|

.

.